Diverted Profits Tax – the new tax

Diverted Profits Tax (“DPT”) is a new tax first introduced by George Osborne in the 2014 Autumn Statement and applicable from 1 April 2015. The rules are complex and are set out in sections 77 – 116 of Schedule 16 to the Finance Act 2015.

The reason for the introduction of DPT was to avert concerns that multinational groups were using tax planning techniques to divert their profits from the UK in order to obtain a reduction in their corporation tax liability.

Whilst DPT has already been applicable for over 10 months many companies will now be seeking to fully understand the operation of DPT to determine whether they are within the scope of this new tax and are thus required to make a notification to HMRC before the required deadlines.

This article considers when and to whom DPT might apply, and outlines in more detail the reporting requirements and the potential implications of being within the scope of DPT.

What is DPT?

DPT is a completely new tax – it is not corporation tax. The rate of DPT is 25%, i.e. it is higher than the current UK main rate of corporation tax of 20% (which will reduce to 18% from 1 April 2020). In addition, the rate of DPT is higher for (notional) adjusted ring fence profits of oil and gas companies (55%) and for banking companies who are subject to the corporation tax surcharge (33%).

In what situations does DPT apply?

The legislation provides for two sets of circumstances in which DPT could apply:

- Case 1 – where groups create a tax benefit by using transactions or entities that lack economic substance (as defined) – the detailed conditions are set out in sections 80 and 81 of the legislation; and / or

- Case 2 – where foreign companies have structured their UK activities to avoid a UK permanent establishment (an avoided Permanent Establishment) – the detailed conditions are set out in section 86 of the legislation.

The rules are extremely complex and there are a number of conditions which need to be met in order for a company to be within the two cases above and therefore potentially be within the scope of DPT, however, the circumstances in which it could be applicable appear to be wide-reaching.

There are particular companies / sets of circumstances which will be outside of the scope of DPT:

- DPT does not apply to small or medium-sized enterprises (“SME”s) as per the EU definition as modified in section 172 of the Taxation (International and Other Provisions) Act 2010. Therefore, DPT does not apply where an enterprise or group has less than 250 staff and either of one of the following financial criteria are met – an annual turnover not exceeding €50 million, or an annual balance sheet (taking gross assets) not exceeding €43 million.

- DPT does not apply to an avoided PE unless annual UK sales are more than £10 million.

- DPT does not apply to an avoided PE if the UK-related expenses (that is, those referable to UK activity) do not exceed £1 million in the 12 month accounting period.

- DPT should also not apply where, essentially, overseas tax is being paid on the “diverted” profits which is at least equal to 80% of the UK corporation tax otherwise payable, unless (for avoided PE’s) there is a tax avoidance motive.

Assuming none of the above exceptions apply, detailed below are two examples of situations in which HMRC consider a company would be within the scope of DPT.

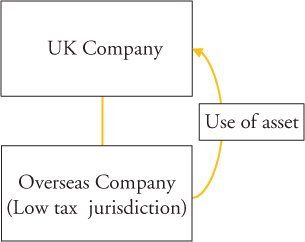

Example 1 – where groups create a tax benefit by using transactions or entities that lack economic substance

Facts:

A UK Company makes use of an asset owned by the overseas subsidiary for which it pays a royalty of £20m (charged through the accounts). The £20m payment would be the “material provision” for HMRC.

The UK Company has pre-royalty profits of £50m which are reduced to £30m after the royalty payment.

The UK Company carries out a transfer pricing analysis and determines that an arm’s length price for the use of the royalty would be £12m, hence its profits have been understated. The taxable profits are adjusted as a result of this analysis and are increased to £38m.

Based on a review of the facts and circumstances, HMRC consider that the “relevant alternative provision” would have been for the UK Company to own the asset itself and therefore there would be no royalty payment made by the UK Company.

The taxable diverted profits are the amount by which the UK Company would have been chargeable to corporation tax for the period had the relevant alternative provision been made or imposed instead of the material provision (if this were the case, the taxable profits would have been £50m). This exceeds the amount in respect of which the company is chargeable to corporation tax following the transfer pricing adjustments (where the taxable profits were £38m) and so results in taxable diverted profits of £12m.

This example shows that the DPT legislation goes further than ensuring the transfer pricing position of the group is correct.

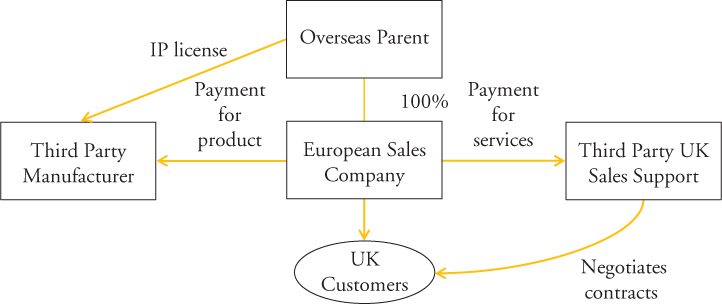

Example 2 – where foreign companies have structured their UK activities to avoid a UK permanent establishment

Facts:

The Overseas Parent manufactures and distributes products with embedded intellectual property.

Sales within Europe are made by a single principal company (the European Sales Company) which is located in a low tax jurisdiction – i.e. contracts are concluded by the European Sales Company. Sales support is provided by a local UK distribution company.

From an examination of the facts and the arrangements in respect of the sales to UK customers, HMRC consider that there is a contrived separation of the conclusion of contracts, i.e. with the UK sales support managing activities such as negotiating the contracts and agreeing of terms and conditions etc. and the European Sales Company simply signing the contracts. HMRC would consider that there is limited value added by the European Sales Company in respect of this transaction and that the requirement of the European Sales Company to conclude the contracts is intended to limit the ability of the UK to tax the profits arising from the activities.

In this situation, HMRC would consider that the group would be within the scope of the DPT legislation on the basis that there is an avoided PE in the UK.

How is DPT administered?

Unlike corporation tax and many other taxes, DPT is not a self-assessed tax. Instead, a disclosure requirement is imposed upon companies who consider themselves to be potentially within the scope of DPT.

The procedure for complying with the DPT disclosure requirement is as follows.The company must notify HMRC if it considers itself to be potentially within the scope of DPT. The notification must be made within three months of the accounting period end. An extended notification period is permitted for the first accounting period of the company in which DPT was introduced and notification can be made up to six months after the accounting period end.

As an example, if a company has a 31 December 2015 period end and considers themselves within the scope of the DPT legislation, notification is required to be made by 30 June 2016. For the period ended 31 December 2016, the notification period shortens and will be required to be made by 31 March 2017.

If a company does not consider themselves within the scope of DPT, it is not necessary to submit a notification to this effect.

What happens after notification is made?

Once notification is made, HMRC may issue a preliminary notice of chargeability to the company. This must be issued by HMRC within two years of the end of the accounting period.

After the preliminary notice is issued, the process picks up pace immediately. The company has 30 days from issue of the preliminary notice to make representations; however HMRC will only consider representations on certain matters:

- Calculation errors in the amount of DPT charged,

- Assumptions on which the diverted profits figure is based and;

- The threshold conditions, for example whether the company is in fact an SME in the relevant accounting period.

Within 30 days of the end of this representation period, HMRC must either:

- issue a charging notice; or

- confirm that no charging notice will be issued.

Should HMRC issue a charging notice, the company is required to pay the DPT within 30 days of the date of this notice. Importantly, the company has no right to request that the payment of DPT is postponed and in the case of non-UK resident companies who fail to make the DPT payment, HMRC have the power to issue a notice to a related company requiring it to pay over the DPT to HMRC within 30 days of the notice.

HMRC have a year from the date the DPT was paid (the “review period”) to review the charging notice which was issued and can either issue a supplementary charging notice or an amending notice – this can either increase or reduce the amount of DPT.

The company has 30 days after the end of the review period to make an appeal. If no such appeal is made, the DPT becomes final.

What happens if companies don’t comply with the notification requirement?

If no notification is made by the company and the company is potentially within the scope of the legislation and as such, should have made a notification, the company may be liable to a tax-geared penalty. In addition, should a company not make a notification where it should have done so, HMRC have an extended period of time to issue a preliminary notice which is four years from the end of the accounting period.

As can be seen from the above, HMRC are afforded much more time to take action than the affected companies have to react to any such action, i.e. the imposition of a DPT charge.

How do companies engage with HMRC?

HMRC have established a “Large Business Task Force” to deal with taxpayers in respect of DPT and to implement the new tax. There is no clearance procedure to follow in order to determine whether DPT may apply, however, taxpayers may be able to enter into dialogue with HMRC to obtain a view as to whether transactions could fall within the scope of DPT.

Conclusion

The rate of DPT, coupled with the taxpayer’s opportunity to challenge a DPT charge along with the timing of payment indicates that DPT could be considered a punitive measure. This is not surprising given that DPT was implemented to dissuade multinational enterprises from entering into contrived arrangements to divert their profits from the UK.

As the tax has only recently been introduced, it will be interesting to watch how it develops and also how it interacts with BEPS, Double Tax Treaties and other measures currently in place in respect of multinational groups such as the UK CFC regime.

Will DPT encourage affected companies to review the structure of their organisation and transactions so they are not caught by these rules?

From HMRC’s perspective, it is quite possible that rather than be significantly tax generative in itself, DPT will be additional ammunition in order for companies to get other aspects of their UK tax compliance in order.

Sarah Fitzgerald is a Manager with PwC UK. Sarah is a Chartered Accountant and Chartered Tax Adviser.

Email: sarah.a.fitzgerald@uk.pwc.com

Website: www.pwc.co.uk