Varney Rebuttal

ICAI - Rebuttal of the Varney Review of Tax Policy in Northern Ireland

Introduction

The purpose of this document is to offer a response and critique of the Varney Review of Tax Policy in Northern Ireland, published on 17 December 2007.

As acknowledged in Appendix F of Sir David's report, the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland (ICAI) made a detailed submission to the Review as a response to its ‘call for evidence’. The evidence provided followed a meeting ICAI had with Sir David and his team at Government Buildings in Dublin on 18 June 2007 in which we emphasised the ICAI's support for a 12.5% corporation tax rate in Northern Ireland by focussing on three key areas:

- An analysis of why a reduced corporation tax rate in Northern Ireland is vital to Northern Ireland's future economic growth.

- An analysis and rebuttal of the technical arguments which have been presented over the years as a rationale for not providing Northern Ireland with a separate corporation tax rate.

- The experience of a low corporate tax rate in the Republic of Ireland.

The ICAI Varney Review Submission is reproduced in the Appendix to this rebuttal.

Executive Summary

The position of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Ireland (ICAI) is that it fully supports the introduction of a reduced corporation tax rate in Northern Ireland to a level of 12.5%, being the same as the rate applicable in Ireland.

We take this view because we believe it is a vital element in stimulating economic growth and productive job creation. We concur fully with Sir David's analysis of the heavy reliance on the Public Sector within the Northern Ireland economy and its relative lack of development in comparison with other regions — indeed we made these points in our submission to him in the context of his first report.

Among the conclusions he draws is the higher level of growth in Northern Ireland in comparison to other regions. While this conclusion is doubtless statistically correct, high rates of growth from a low base are much easier to achieve than continued growth from a higher base. It is this latter challenge which faces Northern Ireland. The key statistic is perhaps that private sector wages in Northern Ireland are less than four fifths of the UK average and among the lowest of the regions in the UK.

Our particular advocacy of a low corporation tax stems from our first hand experience of its effect in the Irish economy, as ICAI is an all-island organisation, with members in Northern Ireland and Ireland. In this regard we would strongly differ from Sir David's evaluation of the impact of a low corporation rate, and we expand on this point later.

ICAI has consistently pointed out that the legal and technical obstacles to providing Northern Ireland with its own corporation tax rate can be overcome. Such obstacles are often presented as a rationale for not doing so. In this regard we welcome the Varney analysis that the legitimate constraints placed by the EU Treaty on the granting of State Aids need not necessarily rule out the establishment of a separate Corporate Tax regime in Northern Ireland. However the Review does suggest that other technical obstacles remain, which we feel merit closer examination.

The Varney Review of Tax Policy in Northern Ireland primarily concerns itself with Corporation Tax, and its discussion does not address Income, Capital and Indirect Taxes. We believe this is a significant shortcoming, as the effect of one particular tax cannot be seen in isolation.

The Review focuses on differences between the Northern Ireland economy and the Irish economy. Whilst there are differences, it ignores the significant similarities in language, culture, education, transport, telecommunications and business legislation. An ‘All Island Economy’ is a reality, accepted by the governments on both sides of the border. Notwithstanding the tendency to focus on differences, the Review does note that the imbalance of corporation tax rates is a significant obstacle to maximising the benefit of this shared Economy — we welcome this recognition.

We note that the Review does not fully explore the possible beneficial effects of other forms of tax incentive to help redress the economic imbalance within Northern Ireland which all commentators, including Sir David, have identified. Whilst a sub optimal solution, it is clear that even some specific tax incentives that do not impact on the main rate of corporation tax would be of some benefit to the Northern Ireland economy as it tries to compete in the global quest for FDI.

Overall, while the Review cogently identifies the challenges (in particular as articulated in the executive summary), it offers little in terms of solutions. A more proactive approach is required, which builds on the potential of the all island economy noted in the Review.The need for a more proactive approach is implicitly recognised from the commissioning by Government of a further report from Sir David.

“Chapter 1 - The Ireland Economies”

Chapter 1 of the Review devotes considerable attention to the role of Corporation Tax in the Development of the Irish Economy (p21) The analysis has some significant shortcomings.

- Varney notes that even though progressive tax measures were introduced in Ireland as early as the 1950s, Ireland was not successful in securing FDI in the technology sector until the 1990s. However it must be remembered that High Tech industry did not proliferate worldwide until the late 1980s. Most manufacturing before then had a high proportion of “low skill assembly and packaging work”. Because of a lack of natural resources, Ireland was never going to attract heavy manufacturing industry. FDI reaching Ireland in the manufacturing sector could only be composed of assembly and packaging — these were among the few manufacturing activities which prior to the mid 1980's were mobile. Among the best examples of this phenomenon is that cited in the Report itself at paragraph 1.54, the case of Apple Computers.

- High value added generates higher profits, but also higher wages, higher dividends and higher expenditure on local goods and services, which in turn feed into the economy.

- Much Irish FDI concerns service industry. Varney seems to identify FDI with manufacturing, which is incorrect. Ireland now accounts for more than 4pc of global services exports but has less than 1pc share of global merchandise, i.e. exports of physical goods.

- Varney fails to distinguish between low Corporation Tax applied to manufacturing activity only (pre 2003) and universally, when analysing the impact of reduced rates in the Irish economy.

- Varney's own examples point to the necessity of creating a skills demand by attracting FDI before putting the education and training infrastructure in place.

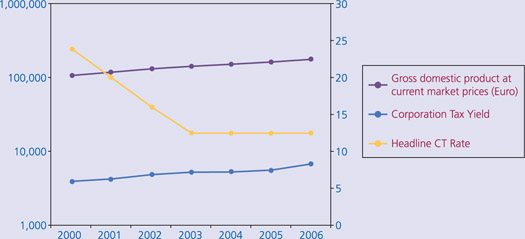

The Irish experience of a reducing Corporation Tax rate is perhaps best exemplified in the graph.

The value of this illustration1 is that it is derived from real life figures, not projections or assumptions. Sir David makes much in his analysis of the elasticities between economic activity and tax yields. However the key conclusion from the Irish experience is that an increase in economic activity, as measured here by GDP, leads to an increase in tax yield irrespective of the applicable CT rate.

We agree with the Review that there is one factor which can skew this conclusion, and that is the risk of displacement of activity between the UK and Northern Ireland. However we are clear that this can be countered and managed, using existing legislation, and we discuss this aspect later in the document.

One final observation on the cost of a lower CT rate - if the Review workings are correct, the annual cost of a reduced CT rate for Northern Ireland is presented as being in the order of £300m annually2. This represents approximately 4% of the annual Exchequer subvention to Northern Ireland. We feel this context is necessary.

“Chapter 2 - Tax and Investment”

ICAI has three particular difficulties with the Varney Review here.

Corporation Tax

In dismissing the role which tax has to play in attracting inward investment, the Varney analysis largely focuses on Corporation Tax. It makes less reference to income taxes, capital taxes and indirect taxes. Of itself, this does not make the analysis incorrect, but taken with the other shortcomings identified below, it suggests serious shortcomings in the chapter's discussion of relevant factors.

Impact of reducing CT Rate – Republic of Ireland

Understanding how FDI decisions are made

At paragraph 2.45, the review concludes, from an analysis of econometric studies, that “the prime motivation for FDI is easy market access with low costs, as well as skills, infrastructure and telecommunications”. We would concur that this is clearly the case.

There are two main reasons why a business might seek to establish a foreign presence with direct investment. The first is that it wishes to broaden its market access outside of its domestic market. The second reason is that it wishes to reduce its cost base, either by accessing a cheaper labour market or a ready supply of raw materials, perhaps natural resources. These account for the business decision to commit to foreign investment.

None of the US multinationals currently trading in Ireland decided in the first instance to invest in Ireland. Rather, they took a decision to establish a presence outside of the US, either for market access or for cost reasons. Once that decision was taken, the process of determining the precise location commenced. It is at this stage that Corporation Tax policy becomes relevant. The Varney analysis fails to recognise the decision making process behind the specific location in which the investment is made and thus ignores the importance that corporation tax rates play in that decision. Specifically therefore we would query the Review's positioning of taxation at Stage 3 of the FDI Decision making process.3

Transfer pricing

The critique of the transfer pricing rules is perhaps unfair. It attempts to justify an underlying assumption that low tax rates encourage profit shifting — i.e. the relocation of taxable profits such that greater amounts arise in low tax jurisdictions. It would be naïve to suggest that low tax rates do not encourage profit shifting, but equally it is naïve to suggest that existing mechanisms in place under international agreements are burdensome or ineffective. To quote from paragraph 2.50, “... the enforcement of these rules requires considerable specialised expertise and imposes significant compliance burdens both for the companies involved and for the relevant tax administrations, in particular when pricing issues concern differentiated (e.g. firm-specific) or propriety (e.g. patents) goods. Also, as the evidence below suggests, transfer pricing rules are not perfect and do not wholly prevent companies from engaging in profit shifting.”

Transfer pricing measures are a necessity wherever there is a discrepancy in rates of tax between countries. The prospect of transfer pricing manipulation has resulted in a network of international conventions, arbitration mechanisms and specific anti transfer pricing rules across the jurisdictions of all developed countries. The main observation we would make in connection with transfer pricing is that it will always remain an issue for countries, irrespective of whether they operate a high or a low headline corporation tax rate.

Transfer pricing rules already exist in the UK, both for connected party transactions between the UK to other countries and for intra UK connected party transactions.

The arguments in the Review are not specific to 12.5% rate proposal, but merely make a general statement on transfer pricing.

We would also point out:

- The introduction of a lower rate regime does not of itself increase or reduce the overall challenge of dealing with the issues which arise. The challenges associated with transfer pricing will only disappear when all tax jurisdictions operate a common CT rate levied on a common base of profits. This solution is not an imminent prospect. In particular —

- The differential in tax rates is immaterial to the operation of transfer pricing rules between countries. Whether the differential is two or twenty two percentage points makes no difference. The procedures and compliance burdens remain the same.

- Protections against transfer pricing under various guises have been in operation for a very long time. They may not, as Varney suggests, be perfect, but they do in fact work. Otherwise they would have been dispensed with or replaced.

- Developments in International Accounting Standards in recent years have gone a very long way towards ensuring that the commercial activities of subsidiaries is reflected properly within corporate groups as a whole. The accounts are the starting point for all computations of tax liability.

“Chapter 3 - Tax and Northern Ireland”

EU Constraints

The Varney analysis agrees with the ICAI position, as submitted by us during the Review process, that the legitimate constraints placed by the EU Treaty on State Aids need not necessarily be an obstacle to the establishment of a separate Corporate Tax regime in Northern Ireland. We welcome this conclusion, but again are disappointed to note that an additional legitimate route in securing EU approval appears to have been overlooked by the Review.

It seems to us that a further approach could be based on Article 87 of the Treaty, which precludes certain forms of State Aid by EU Member States, an approach which was pointed out in the ICAI submission to Sir David in June 2007.

Article 87 operates in a highly regulated and institutionalised way which has evolved by virtue of the powers prompted by the Commission in to Article 88. The fundamental precepts however remain within Article 87. Article 87 3 (b) provides that aid to remedy a serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State may be considered compatible with the common market. Article 87 3 (e) adds that other categories of aid as may be specified by decision of the Council acting by a qualified majority on a proposal by the Commission can also be compatible with the common market.

We would argue that Article 87 could provide sufficient flexibility to allow a distinct CT rate to operate within Northern Ireland, given its very special circumstances, without the United Kingdom being in contravention of the Treaty of Rome.

Implementation Issues

The general theme behind the Varney arguments is that a special tax regime for Northern Ireland would create an additional legal, and hence administrative burdens. The best that can be said to this is to point out that such concerns seem not to influence in any way the publication of annual Finance Acts of increasing complexity, imposing as they do additional administrative burdens.

It seems unlikely to us that the private sector within Northern Ireland would complain unduly about an additional administrative burden arising from an innovative attempt to stimulate the Northern Ireland economy. The Reviews argument against the need to change the standard tax return demands no rebuttal — merely noting it suffices!

Tax Motivated Incorporation

In a low corporation tax regime, individuals should not incorporate to avoid tax. This is achieved by ensuring that the tax penalties associated with cash extraction from companies by individuals outweigh the upfront savings achieved by having had the income taxed in the company's hands in the first place.

In Ireland, undistributed profits retained in a company are subject to surcharges. Distributions are by and large tax neutral, when compared with the taxation regime applied to income earned directly by individuals, but of course are not allowable in computing the company's profits so the aggregate tax take is higher. Income extracted via salary negates the value of the 12.5% CT rate, and attracts higher national insurance costs.

This is achieved by an item of legislation known as the Close Company regime. The version which operates in Ireland was originally derived from UK legislation, and has survived, largely unadjusted, for more than thirty years. It ensures that individuals incorporate their trades or professions for commercial reasons, to benefit from limited liability and to reduce the amount of tax payable on business profits which in turn can be re invested into the business

Therefore Government would not need, as suggested in paragraph 3.32, to design a complicated regime to counter tax motivated incorporation. We think that all that may be required is to re-instate legislation -Income and Corporation Taxes Act 1970 ss282-303 would be helpful in this regard -and localise it for Northern Ireland.

Displacement of Profits

Concerns regarding the possible migration of profit generating activities from the UK to Northern Ireland can also be dealt with through relatively straightforward legislation. We point as an example to the Export Sales Relief legislation for corporates introduced in Ireland inthe 1950s, a precedent of which Sir David is aware because he refers to it in his Review.

In this instance, the concern was to ensure that Export Sales Relief would act as an incentive to companies to establish in Ireland. This aim was met by the simple expedient of denying it to companies already operating in Ireland. A parallel approach could be taken in regard to ring fencing the benefit of a low corporation tax rate within Northern Ireland.

Burden on HM Revenue and Customs

As the UK operates a Self Assessment system, the primary responsibility in accounting for Corporation Tax rests with the taxpayer, not HMRC. The concerns advanced might have carried some weight if Corporation Tax was still assessed directly by HMRC, but it is not.

Tax Treaties

Tax treaties are negotiated to further trade, and at present the UK holds treaties with in excess of 120 countries, the largest network of treaties4 in the world. Suggestions that countries might be unwilling to negotiate further treaties with the UK, a G8 nation, by reason of a special tax rate applying in Northern Ireland are simply not credible.

Alternatives to a reduced Corporation Tax Rate

In his Review, Sir David considers a number of alternative tax incentive arrangements to a reduced Corporation Tax Rate. These include:

- Enhanced Credit Arrangements for Research and Development

- Enhanced Capital Allowances Regimes

- Increased Allowances for Training Costs

- Increased Allowances for Marketing Costs

These suggestions are dismissed in the Review, for reasons ranging between concerns over shifts of activity between the UK and Northern Ireland, to EU compliance issues, and sometimes merely on the grounds of complexity.

However, the most positive reason for the introduction of tax incentives is perhaps not addressed, and that is their role on placing a particular location on the map as an FDI destination.

Every EU Member State, almost without exception, supports zones with enhanced tax incentive arrangements. Worldwide, territories and regions become associated with the economic activity they have chosen to favour, for example Puerto Rico and Singapore for Research and Development activities.

The Review conclusions also apparently run counter to existing research. The Treasury's own conclusions on the R&D Tax Credit (in December 2005) notes that international evidence from other OECD countries strongly suggests that fiscal incentives, such as the R&D tax credit, are effective in generating additional R&D, although their full effects may not be felt immediately. “An effective tax incentive should be visible and predictable, so that firms can build its level of support into their investment appraisal with certainty, and should offer sufficient value to influence those decisions”.5 Even though the Review adverts to this research, it still questions “whether a market-driven tax credit which reduces the cost of business R&D represents good value for money relative to other available policy instruments.”6 This seems at best contradictory.

Another reason for rejecting enhanced R&D credits — that they might fail on EU Treaty grounds — does not appear to be in line with the most current Commission thinking (COM 2006 728)

Although they are far from the best solutions, we suggest that at the very least, alternative tax reliefs be re-examined with the starting point being their viability as a marketing initiative for Foreign Direct Investment.

1. Figures provided by the Department of Finance.

2. At Paragraph C.50.

3. At Paragraph 2.38, “Tax in investment appraisal process.”

4. According to the International area of the Legislation section of Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs website.

5. Supporting growth in innovation: next steps for the R&D tax credit, December 2005.

6. At Paragraph D22.