Don’t lose interest! A summary of the UK’s new rules on interest deductibility

Introduction

For UK corporation tax purposes, there have been measures in place for years which seek to limit corporation tax deductions for interest expenses – for example transfer pricing and thin capitalisation, loans for an unallowable purpose and the worldwide debt cap regime.

Businesses will, of course, have had to take these rules into consideration but may have found themselves not impacted by their operation. However, from 1 April 2017, a new interest capping rule will be introduced in the UK and the same can’t be said about its impact. It is therefore critically important for all UK companies to take action now to ascertain whether they could be affected by these new rules.

The draft legislation extends to over 130 pages. The rules are complex and contain an extraordinary amount of new definitions so this article can be no substitute for a detailed reading of the provisions and a case-by-case analysis being undertaken, however, should serve to highlight some of the main points.

Why is the UK introducing new rules on interest deductibility?

The UK signed up to the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (“BEPS”) project under which the final recommendations were issued in October 2015. At this point, it was left to each participating country to determine the action required to bring the recommendations into law. Action 4 of the BEPS project concerned interest deductibility and a proposal to cap interest deductibility to a percentage of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (“EBITDA”) was recommended.

The UK government was quick to announce that it would introduce legislation to bring to life the recommendations of Action 4. Two consultation processes followed in 2016 resulting in draft legislation being published in the Finance Bill 2017 draft clauses and some further clarity was given on certain aspects of the rules in late January 2017.

What are the key points to know?

The stated aim of the new legislation is to prevent international groups from arranging their intra-group debt to avoid UK taxable profits. Undertaking a review of the rules quickly identifies that they are complex and wide-ranging and can apply to companies regardless of whether they have carried out any tax planning using debt.

It is important to note that these new rules do not replace any of the existing tests on interest deductibility. The new rules are required to be applied after having given consideration to the existing tests. So, for example, even if there is an agreed Advanced Thin Capitalisation Agreement in place with HMRC, there could still be a disallowance of interest under these rules.

The rules could also operate such that there are disallowances for interest even for UK groups with only external debt.

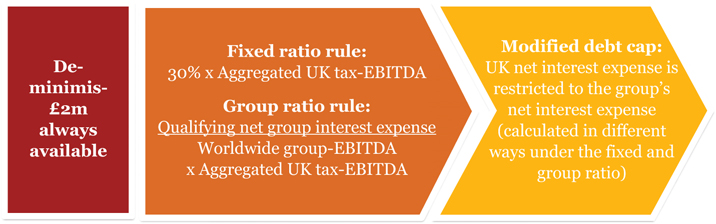

There is a de-minimis exemption which states that if the UK group has less than £2m net interest expense, there can be no disallowance under the rules. This is the starting point of any analysis. Thus, where there is net UK interest expense in excess of £2m, the rules need to be further considered.

For those companies with net interest expense in excess of £2m, there are three main tests contained within the interest deductibility rules:

- The fixed ratio test

- The group ratio test

- The modified debt cap

The fixed ratio

This is the basic rule and provides for the net interest expense of the UK group companies to be capped at 30% of UK tax-EBITDA (EBITDA as defined by the interest deductibility legislation).

The group ratio test

The group ratio is intended to help groups that are highly leveraged for commercial reasons obtain a higher level of net interest deductions. If a group wishes to use this ratio, it is necessary to make an election to do so.

The group ratio enables the 30% limiting factor under the fixed ratio to be replaced with a potentially higher number.

The calculation of the group ratio test requires the exclusion of interest payable on related party debt which is widely defined in the legislation and includes more than just situations where the lender controls the borrower.

The finer details of the group ratio calculation were published in late January 2017 and it is safe to say the provisions are complex and detailed work will need to be undertaken to understand the impact. Broadly, this ratio operates by comparing group EBITDA (EBITDA as defined by the interest deductibility legislation) with interest expense (based on global consolidated accounts but adjusted for UK tax principles).

The modified debt cap

Notwithstanding the limits set by the fixed and group ratios, the modified debt cap is a further potential restriction that must be considered prior to determining whether there is an interest disallowance. The modified debt cap is designed to cap the net interest deduction at the level of the group’s consolidated net interest expense.

Example of how the rules will operate?

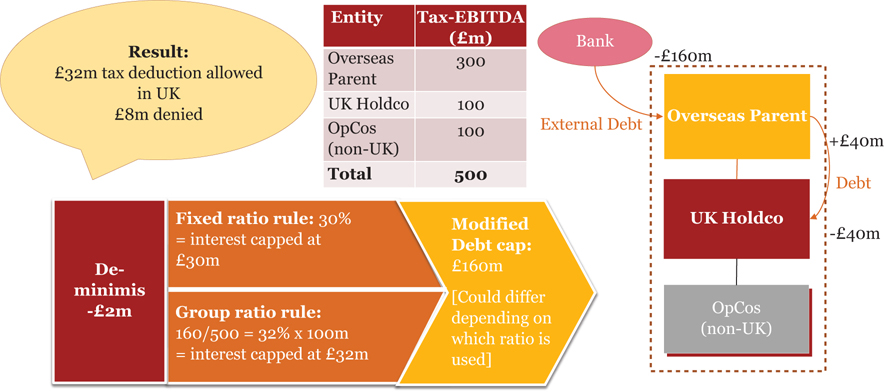

Taking the rules at their simplest interpretation, below is an example of how the tests outlined above would apply in practice.

This example shows an overseas parent company borrowing funds from a bank (i.e. from an unrelated party) and paying interest of £200m on this borrowing. It on-lends a proportion of the debt to the UK Holdco and charges the UK Holdco interest of £40m – what is the impact of the new rules in this particular scenario?

This example demonstrates that the group ratio (being the qualifying net group interest expense of £160m divided by the group Tax-EBITDA of £500m) produces a better result than the fixed ratio (being 30% of the UK Tax-EBITDA of £100m) because the group ratio derives a higher limiting factor. The modified debt cap produces a figure in excess of both the fixed and group ratio, however, this test can only serve to further restrict interest deductibility and it cannot increase it.

What happens if there is a disallowance of interest?

If there is a disallowance of interest as a result of the application of any of the above tests, a tax liability may arise to the extent that interest deductions were previously reducing taxable profits to nil.

It should be noted that disallowed interest does not disappear and there are provisions which state that, where there is a disallowance, the disallowed amount is carried forward and a deduction is available in the future where the tax EBITDA in the future period is large enough to cover both the current year interest charge and all or part of the brought forward charge.

The modified debt cap, mentioned briefly above, still applies in the later period, capping both current and brought forward interest at the level of the group’s current year interest.

Where a company has not sufficient interest expense to utilise what it would otherwise be allowed, for example, where 30% of Tax-EBITDA is greater than the actual net UK interest expense for the period, there are also provisions which enable a company to carry forward this “spare capacity” for up to five years which can help to justify bigger interest deductions in later periods.

Who is impacted?

There is no carve out for small or medium sized enterprises so companies of any size can be impacted by the new rules. There is, however, a de-minimis exemption as noted above, so to the extent the UK group has less than £2m of net interest expense, there can be no impact. This de-minimis was intended to exempt a large number of businesses, however, there are clearly certain sectors which will be more highly geared than others so whilst this might exempt a large number of businesses, there are entire sectors which will not find this exemption helpful.

Initially, there was concern that companies in particular industries who were highly geared for commercial reasons but which pose little risk from a BEPS perspective could be adversely impacted by the new provisions. A further exemption was therefore introduced, the Public Benefit Infrastructure Exemption (“PBIE”) which, if particular conditions are met, enables the company’s third party interest to be exempted from the rules. However, importantly, under this exemption, related party interest remains subject to the fixed ratio or group ratio tests and ultimately the modified debt cap test.

These provisions have been subject to significant debate as they were initially very narrowly drafted and there was a lack of clarity as to how they would operate in practice. HMRC did announce changes to the drafting of the PBIE in the Finance Bill 2017 draft clauses which included broadening the range of industries which could qualify and also introducing an element of grandfathering, meaning that in some very specific situations, interest payable on related party debt can come within the PBIE.

If this exemption is available and a company chooses to avail of it, a prospective election is required to be made. This election is irrevocable for a five year period so it is critically important to consider whether making the PBIE election is beneficial in the particular circumstances of the company in advance of the deadline.

What action should companies take now?

Whilst the legislation is still in draft form, the legislation will come into effect in less than two months on 1 April 2017 and all companies should take some sort of action now.

Some companies will find it relatively simple to analyse the impact, for example if the UK group has less than £2m UK net interest expense, there can be no restriction under these rules. Notwithstanding this, for a lot of companies, the analysis will be much more complex and will initially involve ensuring there is a full understanding of the provisions, how they impact on the specific group and an evaluation of how much the new rules will cost – i.e. how much additional corporation tax will be due.

Companies in particular sectors will need to undertake a detailed analysis to ensure firstly that the strict conditions to qualify for the PBIE are met and secondly to ensure that claiming the exemption results in the optimal position.

Finally, it will be important to understand the documentation and compliance requirements which, as currently drafted, are not simple.

Sarah Fitzgerald is a Senior Manager with PwC and a Chartered Accountant and Chartered Tax Adviser.

Email: sarah.a.fitzgerald@pwc.com